What does the Czech Reformation have to say to today’s Czechs?

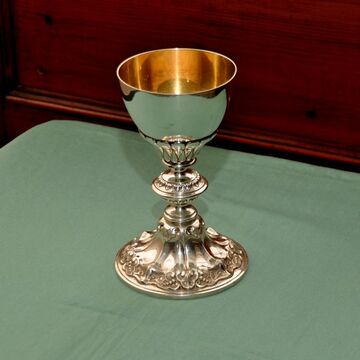

The Protestant Churches are experiencing a period of "big anniversaries": the publication of the Kralice Bible (1613), the first celebration of Holy Communion in both kinds (1414), the martyrdom of Master John Hus (1415) and Jerome of Prague (1416). What do these and other personalities and events of the Bohemian Reformation mean for people today?

The Protestant Churches are experiencing a period of "big anniversaries": the publication of the Kralice Bible (1613), the first celebration of Holy Communion in both kinds (1414), the martyrdom of Master John Hus (1415) and Jerome of Prague (1416). What do these and other personalities and events of the Bohemian Reformation mean for people today?

The Bohemian Reformation began - in terms of their conceptual content - with Hus. Jan Hus started out, on one hand, from the thoughts of the English scholar John Wycliffe (1320? -1384), and on the other hand, he drew on his native predecessors. He rejected the worship of persons and things, announced the superiority of the Bible as the revealed and recognizable truth above other authorities, and was willing to give his life for it. In the interpretation of Czech history, the Bohemian Reformation is usually associated with the Hussite movement, which is considered either as a highlight of Czech history or as destructive movement of vandals. The Hussite Wars, of course, were conducted primarily for the protection of freedom of conscience and the independence of the country against repeated Crusades. The Bohemian Reformation was not violent. Think about Peter Chelčický and his followers, and the later Unity of Brethren. The Hussite Wars were only a brief episode in comparison with the Bohemian Reformation as a conceptual movement. This movement unfolded over two hundred years until the Battle of White Mountain, and bore some remarkable fruit.

The program in the Four Articles of Prague

The Four Articles of Prague were the program of the Hussite movement, to which all Hussite parties agreed in 1419. From the free preaching of the Word of God (1. Article) can be derived the general freedom of speech. Holy Communion in both kinds (2. Article) eliminated the difference between privileged priesthood and the others. The principle that the Church should not have worldly property (3. Article) can be understood as a resistance against the abuse of power and accumulation of property. The punishment of all classes for their sins (4. Article) led to the equality of all citizens before the law. This equality was stressed by the Hussites, and later in the Unity of Brethren, through the use of the title "Brother/Sister" - without distinction of status. We can thus find elements that are directed towards a modern democratic society in the program of the Hussite movement.

Education for All

There is also a corresponding emphasis on education for all. Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini, the later Pope Pius II, was an opponent of the Hussite movement. However, he noted that any Hussite woman knew the Scriptures better than some Roman priests. The desire for general Scripture knowledge led the Hussites, and later the Unity of Brethren, to the effort for a modern Bible translation into the national language, with explanations for laymen (six-volume Kralice Bible 1579-1593, last volume edition 1613) and to the remarkable development of an educational system. In addition to elementary schools, secondary schools also emerged during the Bohemian Reformation (for example, one school in Prague near the Salvator Church was financed, by Peter Wok von Rosenberg). One highlight of the intellectual aspirations of the Bohemian Reformation was Comenius. His comprehensive effort for a better organization of all human knowledge still demands respect even today.

Religious Tolerance

Unusual features of the Czech Reformation were their peace efforts and religious tolerance. Its precursor was already Peter Chelčický, who opposed violence in the midst of the Hussite wars. (From Chelčický goes an interesting way of nonviolent thought through history: Chelčický demonstrably influenced Tolstoy, Tolstoy influenced Gandhi, and Gandhi, in turn, M.L. King, Jr.). George of Poděbrady tried in 1462 to find a peaceful unification of Europe - a union that resolves its internal disputes by negotiation, not by war. At home, George urged the warring sides to peace and after his death came the conclusion that differences of faith cannot be solved by battle, the provincial law (Religious Peace of Kuttenberg, 1485). This law led, in this country, to equality between Catholics and Utraquists even before the Reformation in Europe, and thus the wars of religion began. Quite exceptional was also the common confession of two Church organizations: the Church in both kinds, and the Unity of Brethren created in 1575 a joint Bohemian Confession. The Letter of Majesty by Emperor Rudolph II from 1609 finally confirmed the freedom of religion also for subjects. This was something cataclysmic in a time when cuius regio, eius religio, which meant that the subjects had to adapt to the faith of their overlord, whichwas the principle everywhere.

The Bohemian Reformation was suppressed with violence after the Battle of White Mountain, but its influence remained strong. Brethren hymns, which had been adopted already in the 17th century by Catholic hymnbooks, continued to resound. Both the national rebirth and also the modern Czech society (especially TG Masaryk) felt a connection with the spiritual content of the Bohemian Reformation. But to what extent are these ideals still valid today? All visions of the Bohemian Reformation - emphasis on social equality, education, freedom of conscience, tolerance and the search for peace – have become, over centuries, within the Euro-American civilization, a given part of their intellectual world. Nevertheless, it must always be fought anew for its realization.

Truthfulness

In the Bohemian Reformation, there was still something else fundamental that we today, as it seems, gradually lose sight of. This is the emphasis on fidelity to the revealed truth which has become manifest (at its most expressive, witnessed by Hus – despite the council that silenced him and sentenced him to death). This truth was certainly not understood in the sense of present considerations, according to which "each one has his own truth." Hus had the truth of the Lord in mind, which we do not possess and that is above all, a higher principle which is binding on the conscience and wins in the end. This truth of the Lord we may recognize, or rather, the truth of the Lord reveals itself to us when we seek it humbly. And then we need to confess this truth, to live according to it, and to defend it to the death, even if it is "sometimes, for a time, defeated" (as George of Poděbrady allegedly stated).

The current Euro-American civilization is at risk, because it loses its unifying ideals. If a higher principle, which is above the individual, is absent, moral values will be relativized and goals blurred. An old wisdom, however, teaches that the one who waives higher goals, has also no success with smaller ones. The Bohemian Reformation, led by the ideal of a superior truth, could see far ahead. In an attempt to implement some of these ideals, a high price is usually paid, as the history of the Bohemian Reformation showed clearly. Nevertheless, it should not be abandoned because of the disintegration of common values or the abandonment of these will threaten the existence of society.

This text was written with the participation of members of the Advisory Committee on Social and International Issues: Miloš Calda, Jan Čapek, Gerhard Frey-Reininghaus, Jindřich Halama, Daniela Hamrová, Miloš Hübner, Ladislav Pokorný, Tomáš Růžička and Daniel Ženatý chaired by Zdeněk Susa.